Accessibility must be embedded in every initiative we undertake as professionals. It’s no coincidence that laws are becoming stricter: ensuring access to digital products and services for everyone is no longer optional—it's a responsibility. In the European Union, this duty is reinforced by the European Accessibility Act, which comes into effect on June 29, 2025, and sets mandatory requirements for digital products and services, both public and private.

In my book, "SXO: Optimización de la experiencia de búsqueda con SEO y UX" (SXO: Search Experience Optimization with SEO and UX), written in Spanish, I dedicate an entire chapter to accessibility, as I believe it is a fundamental pillar for delivering an inclusive and effective digital experience. Understanding what accessibility is and how it directly impacts our work is essential for creating projects that work for everyone.

Do you want to know what accessibility is, how to audit it and how it affects you as an SEO or digital marketing professional? Then keep reading.

What is accessibility?

In Spain, the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Their Social Inclusion (LGD) defines universal accessibility as "the condition that environments, processes, goods, products and services must meet so that all people can participate independently and with equal opportunities." In other words, digital accessibility ensures that anyone, regardless of their abilities, can navigate a website on equal terms. It's not just about complying with regulations or optimizing business outcomes: it's about inclusion, respect and dignity. Designing an accessible website means committing to a fair digital experience for everyone, without exceptions.

Why we need to go beyond the "user persona"

When talking about accessibility, we need to go beyond the concept of the “ideal user” or “user persona” that we so often use in marketing: “María, 23 years old. University student, loves yoga and shopping online.” While this model can be useful for segmentation, it becomes dangerously simplistic when dealing with accessibility. Why?

It simplifies human diversity

A person with a visual disability can also be “María, 23 years old,” but their browsing experience rarely shows up in the user profiles we use to shape marketing strategies. People are not static archetypes: their abilities fluctuate due to age, technological context, or even temporary fatigue.

It ignores situational disabilities

Does your “user persona” include a parent browsing with one hand while holding a newborn baby? Or an executive checking data on their phone outside in bright sunlight? These contextual limitations affect any user, and it’s important to take them into account.

It creates false averages

The “ideal user” doesn't exist. According to a study commissioned by Microsoft and conducted by Forrester Research, 57% of computer users in the United States benefit from using accessible technologies. Surprisingly, 32% of those who use these features do not have any diagnosed disability, which shows that accessibility also improves the experience for users without obvious disabilities, such as those with temporary or situational impairments (defined later in this article). Designing only for the “typical case” means unintentionally excluding a large portion of users who need or prefer to use these features.

It’s reactive, not preventive

“User personas” are usually based on users who already access the product, leaving out those who face barriers. Accessibility requires designing with people in mind who still cannot use it.

Why accessibility matters: Data and opportunities

Designing an accessible website means anyone can browse, understand and use it—whether with a screen reader, keyboard, touchscreen, or voice assistant. And this isn’t just an ethical gesture or legal obligation: it’s also a smart strategy. In the European Union, more than 100 million people have some form of disability. That’s one in four adults. And just in Spain alone, there are more than four million.

If your digital product aims to reach just 1% of the European population, that means potentially one million people with disabilities interested in it. If 100,000 of them become customers and pay a subscription of €9.99 per month for your product or service, we’re talking about approximately one million euros in monthly revenue. The numbers speak for themselves. Are you still thinking accessibility is a luxury? Or maybe it’s time to start having these kinds of conversations with your stakeholders if you haven’t already?

The problem is that accessibility is often still seen as an “extra” rather than the human right it truly is. But beyond being an ethical and legal obligation, it’s an investment that delivers tangible returns. That said, accessibility isn’t a checklist you can complete in a day, nor something you can fully delegate to a tool. It requires commitment, training and ongoing collaboration between design, development, content and strategy. You don’t need to be an accessibility expert to get started — what matters is incorporating an inclusive mindset into your daily work. You can begin by auditing your website with basic tools, checking color contrasts, adding alt text, properly labeling buttons and avoiding unnecessary barriers. And as the project grows, yes, having support from accessibility specialists or even legal advice will be key, but the most important thing is for you to take the first step from your role.

What is disability? Is it a synonym for “accessibility”?

Often the terms “disability” and “accessibility” are confused, but they don’t mean the same thing. Disability refers to a person’s functional limitation; accessibility, on the other hand, is about how we design environments, products and services so those limitations don’t become barriers. A person with a disability can function completely independently if the environment, whether physical or digital, is well designed. For example, someone who uses a wheelchair can move autonomously in an office if it has ramps, automatic doors and accessible restrooms. The same goes for clothing: depending on how it’s designed, a garment can help you dress yourself independently or, on the contrary, become an obstacle. That’s why it’s especially positive to see some brands starting to integrate accessibility into their designs. A good example is Fred Perry, which recently launched an adaptive version of their iconic M3600 polo shirt. The garment keeps its classic design but replaces buttons with magnetic closures, allowing it to be fastened with one hand:

Similarly, if a website is built following good accessibility practices, a person with visual impairment, for example, can navigate it without barriers using a screen reader.

In both cases, physical and digital, accessibility doesn’t eliminate disability, but it does reduce its impact on people’s daily lives. And ultimately, that improves dignity, autonomy and inclusion for everyone.

What types of disabilities exist?

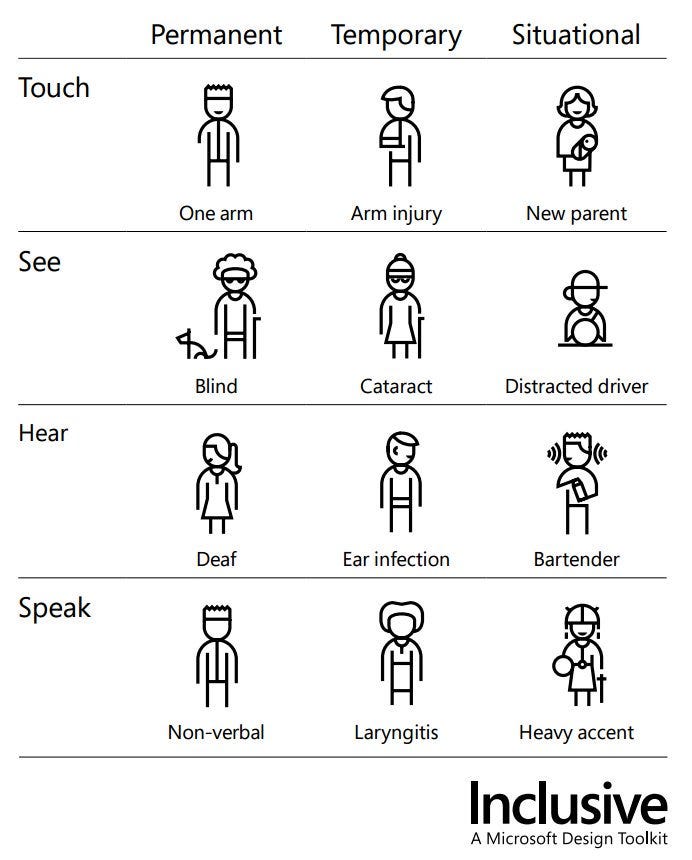

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies disabilities into various categories: physical, sensory, cognitive, mental and developmental. However, in the collective imagination, we often think only of permanent conditions like blindness or deafness. That view is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s interesting to highlight how Microsoft approaches this, as they offer a much broader perspective, noting that disability can also be “a contextual issue, a mismatch between the person and their environment.” According to this perspective, the spectrum of disability is very diverse, and the needs and preferences of each individual vary. They also point out that “at some point, we can all experience some form of disability,” and note that it “can affect aspects such as vision, hearing, mobility, mental health, neurodiversity and speech,” and that it can be “permanent, temporary or situational.”

According to Microsoft’s perspective, disability can also refer to temporary or specific situations where a person is at a disadvantage. For example, when you have a slow internet connection in the middle of a work meeting that keeps cutting out or when a migraine temporarily incapacitates you—these would be examples of a situational or temporary disability. Microsoft addresses this idea in their guide "Inclusive Design," which focuses on how people interact with technology and their environment in different contexts. Their approach aims to recognize that we can all face some form of disability at different times, and that as professionals, we should design more accessible and usable experiences for everyone. Additionally, the company emphasizes the importance of aligning with the principles of universal design, whose goal is to create products and environments accessible to the largest possible number of people, regardless of age, ability or circumstance.

Types of disabilities according to Microsoft

According to Microsoft’s model, disabilities can be classified into three groups:

Permanent disability

- Motor: for example, a person who has lost an arm and faces difficulties performing tasks that require the use of both hands.

- Visual: a person who is blind and cannot perceive their surroundings through sight.

- Auditory: a person with total or partial deafness who has a constant hearing loss.

- Communicative: someone who has permanent impairments to communicate verbally, such as a mute person.

Temporary disability

- Motor: someone with a broken arm that limits their mobility for a period of time.

- Visual: a person with cataracts whose vision improves after medical treatment or surgery.

- Auditory: someone suffering from an ear infection that temporarily affects their hearing ability.

- Communicative: a person with laryngitis who has difficulty speaking while the condition lasts.

Situational disability

- Motor: a mother who has her hands full holding a baby, limiting her mobility.

- Visual: a driver who becomes distracted or loses focus, for example, when checking a GPS.

- Auditory: a waiter working in a noisy environment who struggles to hear customers.

- Communicative: someone with a strong accent that makes comprehension difficult in certain contexts.

How to audit web accessibility: WCAG

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) are the international standard for ensuring digital products are accessible to all people, including those with disabilities. Developed by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) of the W3C, these guidelines are structured around four fundamental principles:

- Perceivable: information and user interface components must be presented in ways users can perceive.

- Operable: user interface components and navigation must be operable.

- Understandable: information and the operation of the user interface must be understandable.

- Robust: content must be robust enough that a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies, can reliably interpret it.

Each principle breaks down into specific guidelines, which are further divided into measurable success criteria. These criteria are grouped into three levels of conformance:

- Level A: minimum requirements that must be met to avoid significant barriers.

- Level AA: intermediate requirements that address the most common issues and affect the largest portion of the population. This is generally the level required to ensure adequate and legally recognized accessibility in most countries.

- Level AAA: optimal requirements that provide the best possible experience for all users.

The latest version of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) is 2.2, officially published by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) on October 5, 2023. This update introduces nine new criteria that expand and complement those of previous versions, improving accessibility for people with visual, auditory, motor and cognitive disabilities. Among the new criteria, some specifically address the needs of neurodivergent users, such as those with ADHD, autism, dyslexia or dementia. For example, criteria were added that require the option to pause, stop or hide moving content, allow modification of time limits, and provide consistent help in predictable locations.

It’s important to highlight that WCAG 2.2 is the latest version in the 2.x series. The W3C Accessibility Working Group has begun focusing on developing WCAG 3.0, which is expected to be a completely new standard with a different conformance system. Future updates to European regulations will likely consider WCAG 3.0, since digital accessibility is a priority in EU legislation. Therefore, it’s advisable for companies—both public and private—to familiarize themselves with these guidelines and consider implementing them to improve the accessibility of their websites and applications, anticipating possible legislative changes and enhancing the experience for all users.

European Accessibility Act (EAA): What is it and why does it affect you?

On June 28, 2025, the European Accessibility Act (“EAA”) will come into effect. This is an European Union directive (2019/882) that sets mandatory requirements for digital products and services, both public and private. Its goal is to ensure that people with disabilities, as well as older adults and other groups with functional limitations, have equal access to a wide range of services and products, including websites, mobile apps, e-commerce platforms, ATMs, banking services, public transportation, and electronic devices such as smartphones, TVs and e-readers.

What are the consequences of non-compliance with the EAA?

Non-compliance with the EAA can lead to significant penalties that vary by EU member state. For example, in Ireland, fines can reach up to €60,000 and include prison sentences of up to 18 months. In Germany, sanctions for failing to comply with the EAA can reach up to €500,000. Beyond fines, companies may face mandatory audits, product or service recalls and reputational damage.

Scope of application

The EAA covers a wide range of products and services, including:

- E-commerce platforms.

- Banking and financial services.

- Public transportation and related services (e.g., websites, mobile apps, ticketing services).

- Electronic devices such as smartphones, tablets, televisions and e-readers.

- Self-service terminals and ATMs.

- Telecommunications and audiovisual media services.

- Emergency and telephone assistance services, such as 112.

It’s important to note that the EAA is not limited to the public sector; it also applies to the private sector, especially in key areas like e-commerce, banking and transportation. Moreover, this regulation affects not only EU member countries but also all companies and organizations operating within EU territory, regardless of their country of origin. This means any entity offering digital products or services accessible to users in the European Union must comply with the requirements established by the EAA.

What is expected from companies?

To comply with the EAA, companies must:

- Adopt the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1, Level AA, as the minimum standard for digital accessibility.

- Develop and maintain a public accessibility statement detailing compliance with the EAA and mechanisms for reporting accessibility issues.

- Implement feedback mechanisms so users can report any accessibility barriers they encounter.

- Conduct regular accessibility audits and document compliance efforts.

- Ensure customer service channels, such as phone systems and online forms, are accessible to people with disabilities.

- Guarantee that digital documents, such as contracts and invoices, are readable through assistive technologies.

How to get started?

To prepare for the EAA, consider the following steps:

-

- Accessibility audit: conduct a thorough evaluation of your digital assets to identify and fix accessibility issues.

- Team training: educate designers, developers and content creators on the WCAG and EAA requirements.

- Implementation of internal policies: establish standards and procedures to integrate accessibility throughout all stages of design and development.

- Ongoing monitoring: implement monitoring tools to ensure continuous compliance and make adjustments as needed.

Other relevant legislation

Did you know that the EAA isn’t the only accessibility law to keep on your radar? If you work with digital products used outside the EU (or if you just want to do things right), it’s important to know other key regulations such as the ADA in the United States or the Equality Act in the United Kingdom. While the EAA has established a mandatory legal framework in Europe, other countries have had legal frameworks in place and active for years.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) also applies to the digital environment. Although it does not specify technical standards, courts have ruled that failure to comply with the WCAG can be considered a violation. In 2023 alone, there were more than 4,600 lawsuits related to web accessibility. Additionally, there are federal laws such as Section 508 (which requires public agencies and government contractors to comply with WCAG) and Section 504, which extends accessibility requirements to entities receiving federal funding. Some states, like California, have enacted their own laws with stricter criteria and specific penalties.

In the UK, the Equality Act 2010 prohibits digital discrimination, and since 2018, public bodies are legally required to ensure their websites and apps are accessible. They must comply with WCAG, publish a visible accessibility statement, and keep channels open for users to report issues. Non-compliance can lead to fines and legal action, as well as harm to the reputation of each company or institution.

If your product has users in countries outside the European Union, it’s not enough to comply with the EAA—you also need to understand the legal requirements of each market.

Tools and resources to verify web accessibility

Although ideally you would have accessibility experts and a legal team to ensure optimal implementation, we can all start taking steps to make our digital products and services more accessible. Testing and using the right tools from early stages helps identify barriers and improve the experience for everyone.

Manual testing with users

User testing is essential to detect accessibility obstacles that automated tools don’t always catch. Some recommended practices are:

- Keyboard-only navigation: use the Tab key to move forward between interactive elements and Shift + Tab to move backward. This simulates the experience of users who cannot use a mouse.

- Use of screen readers: activate a reader like NVDA or VoiceOver on Apple devices and perform common tasks to understand how content is perceived when read aloud.

- Testing on different devices and browsers: verify that the site works correctly across various platforms and configurations, including mobile devices and browsers with accessibility settings enabled.

- Involve people with disabilities: invite users with different disabilities during early design and development phases. If you don't know where to find them, you can reach out to NGOs, schools or support groups, even through communities on Facebook, Reddit or other social networks.

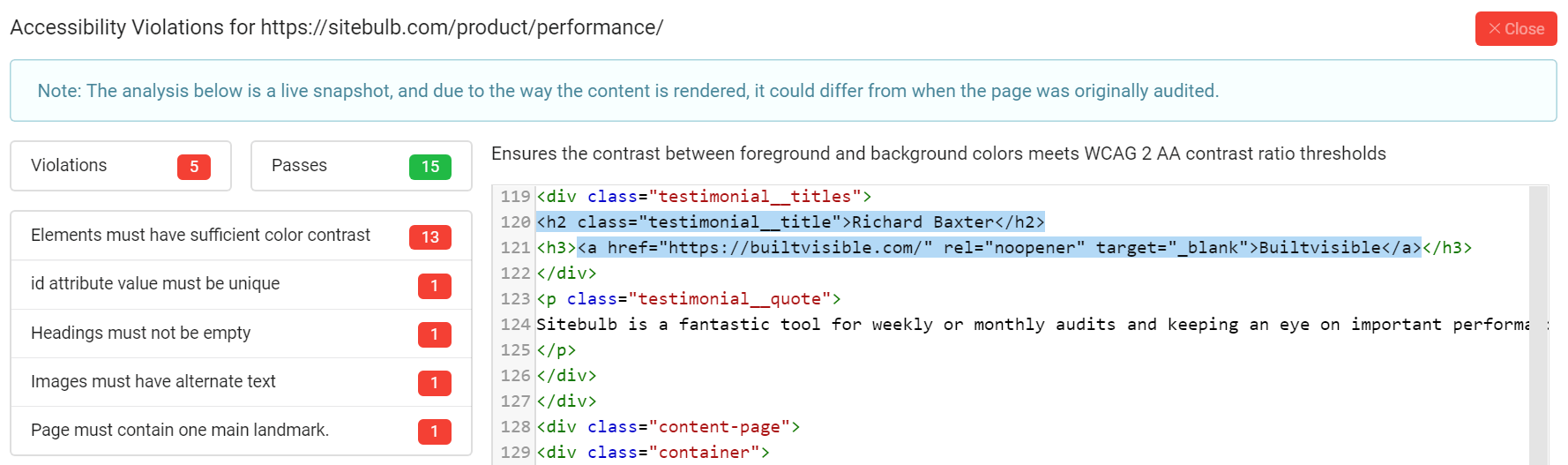

Evaluation tools

Tools are a good complement for detecting common issues. Some of the most useful ones we can use are:

- WAVE (Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool): an online tool that analyzes web pages and flags errors and warnings directly on the content using icons and highlights to make identification easier. It is also available as a Chrome extension (WAVE Evaluation Tool).

- Sitebulb: a very versatile SEO tool that I often recommend for all types of audits and analyses. It allows detailed accessibility audits at scale. It can be configured to evaluate according to different WCAG standards, ideal for complex projects or sites with many pages.

- Screaming Frog: since version 21.0, it offers the ability to perform accessibility audits based on AXE rules, ideal for analyzing large websites with multiple pages. It provides scores per page according to WCAG.

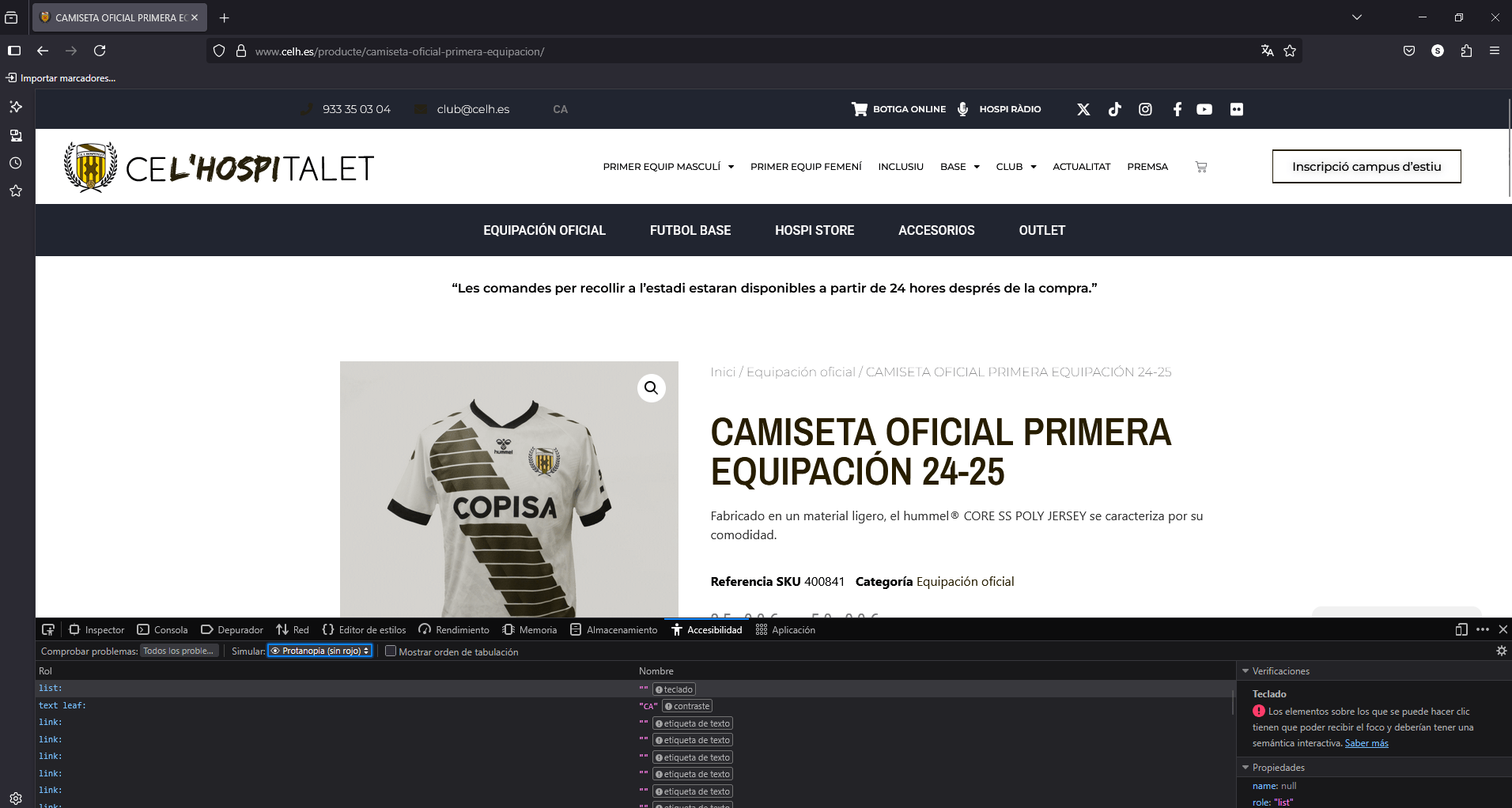

- Mozilla Firefox: includes built-in accessibility tools in the browser. To use them, right-click on a page and select “Inspect.” In the panel that appears, choose the “Accessibility” tab. From there, the “Check Issues” dropdown analyzes aspects like contrast, labels and clickable elements. Additionally, the “Simulate” dropdown lets you see how the page would look to someone with different types of color blindness, such as protanopia or achromatopsia.

- Google Chrome: Chrome also includes an accessibility tool within its developer tools. To access it, right-click on the page and select “Inspect,” then go to the “Lighthouse” tab. There you can run an analysis that includes performance, best practices, SEO, and accessibility. When completed, it shows a score and recommendations to improve accessibility.

Useful extensions and add-ons

Besides desktop or browser tools, there are Chrome extensions and specific plugins for CMSs like WordPress that make accessibility evaluation easier in real time. These add-ons allow simulating experiences of users with disabilities, detecting errors and applying improvements directly on the content.

- axe DevTools - Web Accessibility Testing: once installed, it adds a tab in the browser’s developer tools (DevTools) from which you can run an accessibility analysis. The tool highlights errors directly in the DOM, explains why they are problematic and offers recommendations to fix them according to WCAG.

- Colorblindly: simulates up to eight different types of color blindness. It is especially useful to check how the interface looks to users with visual impairments such as protanopia (no red), deuteranopia (no green) or achromatopsia (no color). This way, the visual design can be adapted to ensure a better experience for all users.

- WordPress Accessibility Checker: a WordPress plugin that allows scanning content while editing. It works similarly to WAVE but integrated directly into the WordPress editor, allowing you to identify and fix errors in real time. It also offers the option to generate large-scale accessibility reports covering multiple pages and posts on the site.

Accessibility widgets: Why they’re not the solution

You’ve probably seen those buttons on websites that activate accessibility tools like font size adjustments, contrast toggles or text-to-speech. These widgets or plugins seem like a quick and easy solution to adapt design for different needs and meet certain requirements. However, these elements are nothing more than superficial patches. True accessibility goes far beyond changing visual aspects or adding a plugin: creating a truly accessible website means designing from the start with all users in mind, including those who use assistive technologies or have limitations.

There is a misconception that these widgets guarantee compliance with accessibility standards, but the reality is they do not. True compliance requires thoroughly reviewing the site structure and ensuring the content is clear and understandable for everyone. Can a widget, for example, adapt the language to make it more accessible? No, that requires much deeper work. These tools promise a lot but deliver little in practice and don’t replace the effort needed to build a truly accessible digital experience. As website owners, SEOs and designers, we must go beyond superficial solutions and ensure accessibility is integrated from the initial design, without relying on patches that don’t solve the root problem.

Essential SXO recommendations to improve accessibility

While digital accessibility is a broad and ever-evolving field, there are a few basic practices that every SEO and UX professional should apply from the start. These aren’t the only ones, by any means, but they’re a solid starting point for making your work more inclusive. And if you’d like to go deeper, in my book, "SXO: Optimización de la experiencia de búsqueda con SEO y UX" (in Spanish), I dedicate an entire chapter to these topics, with practical examples and more advanced recommendations:

- Use clear and straightforward language: avoid unnecessary jargon. Plain language improves comprehension for everyone, including people with cognitive or reading difficulties. It also makes it easier for search engines to understand your content. If you need to use technical or complex terms, link to their definitions. And if you have your own content explaining them in depth, even better—this enhances your internal linking, improves site structure, and offers a more complete experience to your users.

- Avoid complex metaphors: metaphors can sound creative, but they often hinder understanding, especially for people using screen readers or automatic translation tools. The clearer and more universal your message is, the better.

- Use a clear structure with headings and lists: organizing content with hierarchical subheadings and lists makes navigation easier. This is especially important for users who browse with a keyboard or assistive technologies.

- Ensure good color contrast: text should stand out clearly from the background so it’s legible for people with low vision or color blindness. Don’t rely on visual design alone—check contrast using tools like WebAIM’s Contrast Checker.

- Avoid dense blocks of text: long paragraphs can be a barrier for many users. Break content into smaller, more manageable chunks to improve readability, information retention, and scannability.

- Prioritize responsive design: your content should adapt properly to all screen sizes. A responsive design not only improves technical accessibility—it also enhances the user experience and is key for SEO.

- Don’t rely on color alone to convey meaning: if you use color to indicate a status (e.g., someone being online in a chat), pair it with text ("online"). This ensures the information reaches all users, regardless of their color perception.

Best practices for an effective web accessibility audit

To carry out an effective web accessibility audit, consider the following recommendations:

- Conduct regular audits: accessibility is not a one-time goal; it should be part of the ongoing development and maintenance cycle of a website.

- Document and communicate findings: keeping a clear, structured record of detected issues and solutions makes tracking easier and improves collaboration with development and design teams.

- Prioritize issues by impact: not all accessibility issues have the same level of severity. Prioritize those that most affect users.

- Include both manual and automated evaluation: combine tools with manual reviews to detect problems machines can’t catch, like content meaning or logical navigation order.

- Involve real users: tools are useful, but testing with real users provides much more valuable insight into your website’s accessibility experience.

- Consider mobile accessibility: don’t forget many users access from mobile phones and tablets and an accessible experience must be ensured across all devices.

- Stay updated: accessibility guidelines and best practices evolve and will continue to do so. Keep informed about the latest WCAG updates and other relevant regulations.

Final thoughts

Web accessibility is not just about following a checklist of best practices, but a constant commitment to creating experiences that truly work for the maximum number of people. It’s not just about SEO, business or legal compliance; it is, above all, a matter of respect. Designing with accessibility means recognizing that every user matters, regardless of physical, cognitive or technological limitations. It is not only a technical challenge but an ethical responsibility. Digital accessibility is a human right, and making our sites accessible is a concrete way to promote inclusion. That’s why accessibility must be integrated into every decision we make about design, content and development, not treated as a one-off task.